The Republic of Lebanon has a newly elected President. However, unlike most countries, Lebanon operates a complex and sectarian – or confessional – parliamentary system. Something worth exploring to better understand the crucial next steps now that a president has been elected.

Lebanon’s parliamentary system is unicameral – meaning it has one parliamentary chamber, unlike other systems such as the United States Congress and the Westminster system.

It has three branches of government: the Legislative – a 128-member Assembly elected by the people of Lebanon (and eligible Lebanese diaspora around the world); the Executive – a Council of Ministers elected by the National Assembly and based on a simple majority; and the Judicial – a court system that blends sectarian and religious systems.

The Seats – a closer look at voting for the 128-member National Assembly.

A 128-member National Assembly is elected by the people of Lebanon. The last parliamentary election was held in May 2022.

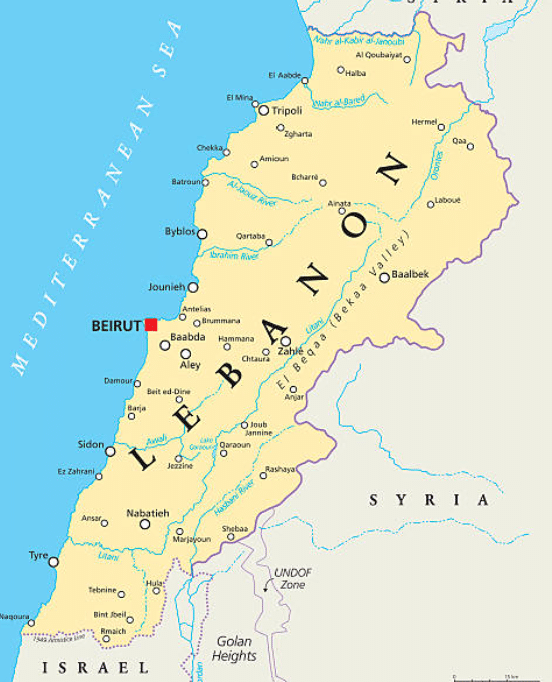

Representation in Lebanon occurs across 15 major electoral districts, called ‘qada’at,’ and 26 minor districts. Voter demographics vary across these districts, leading to ongoing discussions about electoral boundary reform and the potential for merging districts.

The European Union, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and German Cooperation, along with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), report that in the last election, the distribution of seats in the National Assembly ranged from 5 to 11.

So, in each district, electoral regions may have up to 11 seats in Parliament.

The Sects

All seats in each region are allocated based on Lebanon’s confessional quota system. The confessional quota system is there to ensure that the diverse religious and ethnic interests are represented in parliament.

Depending on the electoral region and religious representation, the seats are further divided into Muslim party candidates – including Sunni, Shia, Druze, and Alawite – and Christian party candidates – including Maronite, Greek Orthodox, Greek Catholic, Armenian Orthodox, Armenian Catholic, Evangelical, and minority sects.

So, if there are 10 seats prescribed to an electoral division, and subdivided based on the following sects – 5 Christian Maronite, 3 Shi’ite and 2 Alawaite – a candidate representing another religion will not be considered for election to Parliament for that area.

The highest voted candidates per each party are then elected for the region as deputies to form the 128-member Assembly.

What we can expect to happen in Parliament now

The President (now newly-elected Joseph Aoun) is expected to consult with the deputies (elected candidates) of the National Assembly, to nominate a Prime Minister.

The successful Prime Minister will work with the Speaker and the President, to likely form the 30-member cabinet. This sectarian distribution described above is also maintained across the Council of Ministers.

Lebanese citizens of any other religion are unable to be elected to Parliament.

Critics argue that this structure has led to instances of monopolisation of the economy and governance of the public service, particularly in the energy and defence portfolios—two key areas of reform that the newly elected President Joseph Aoun has vowed to prioritise.